We are still waiting for the 4th batch of sequences/taxonomies and are incorporating more data from different sources for our NCT03582826 study, but have already started looking at the available data.

Our previous trials showed that while there is no one-size-fits-all solution to MEBO and PATM symptoms, some metabolite measurements and self-reported data can distinguish different subtypes of these conditions with very high accuracy.

Hence, we may need different treatments for sufferers with different metabolism - for example, abilities to process sugar in their food or higher production of putrescine in urine (could it be due to pseudomonas and enterobacteria in the gut?).

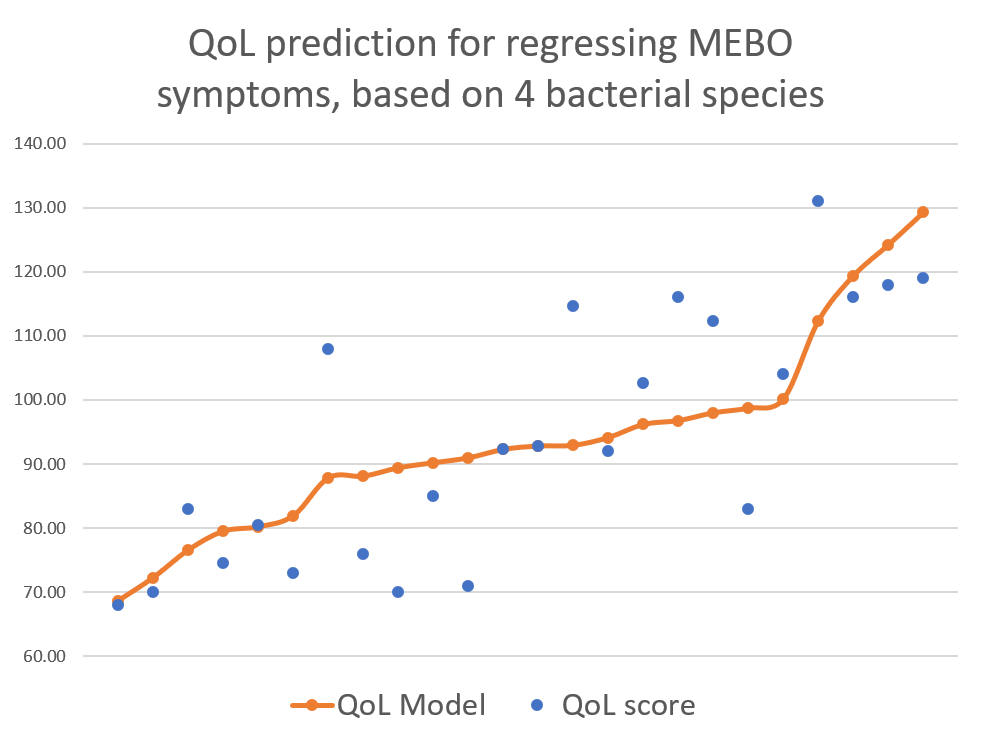

Our previous studies had much fewer variables differentiating MEBO subtypes and fewer participants (NCT02692495: 16 viable samples from 11 men and 5 women; NCT02683876: 15 viable samples from 10 women and 5 men). We are now collecting the biggest ever MEBO dataset for the current study, NCT03582826, with about 5 times larger number of participants than previous studies. One of the questions asked in QoL survey was whether participant's condition was

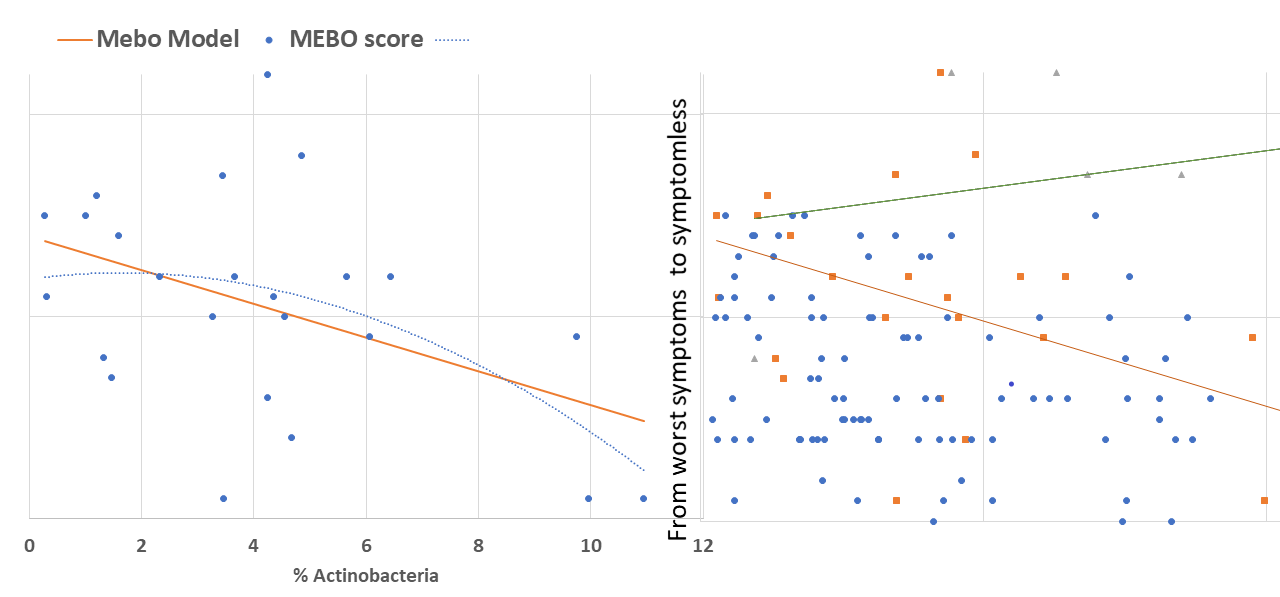

active/progressing, regressing or they were in remission. We decided to start our exploratory analysis from the subset of sufferers with "disappearing" symptoms - when participants felt they were on the road to improvement. The figure above shows a quick-and-dirty model describing how compositions of just 4 microbial classes could predict quality of life for these participants. Interestingly, these bacteria did not seem to be responsible for their MEBO or PATM symptoms, only overall wellbeing. The figure on the left shows how just one phylum of bacteria - Actinobacteria - correlates with the severity of MEBO symptoms in those whose condition is improving. It's very noisy, but it seems that increasing numbers of this bacteria (responsible for the pleasant smell of rain) helps to improve odor. Yet, look what happens when we throw in data from those with active disease or in remission (right section of the figure above) - the pattern is completely lost. Even more so, looks that those who already achieved remission care less about this bacterium and sometimes even slightly benefit (at least, in their own opinion) if they slightly reduce its population. Obviously, we need to subdivide the data better before attempting to build predictive models and look at a lower level of microbial hierarchy.

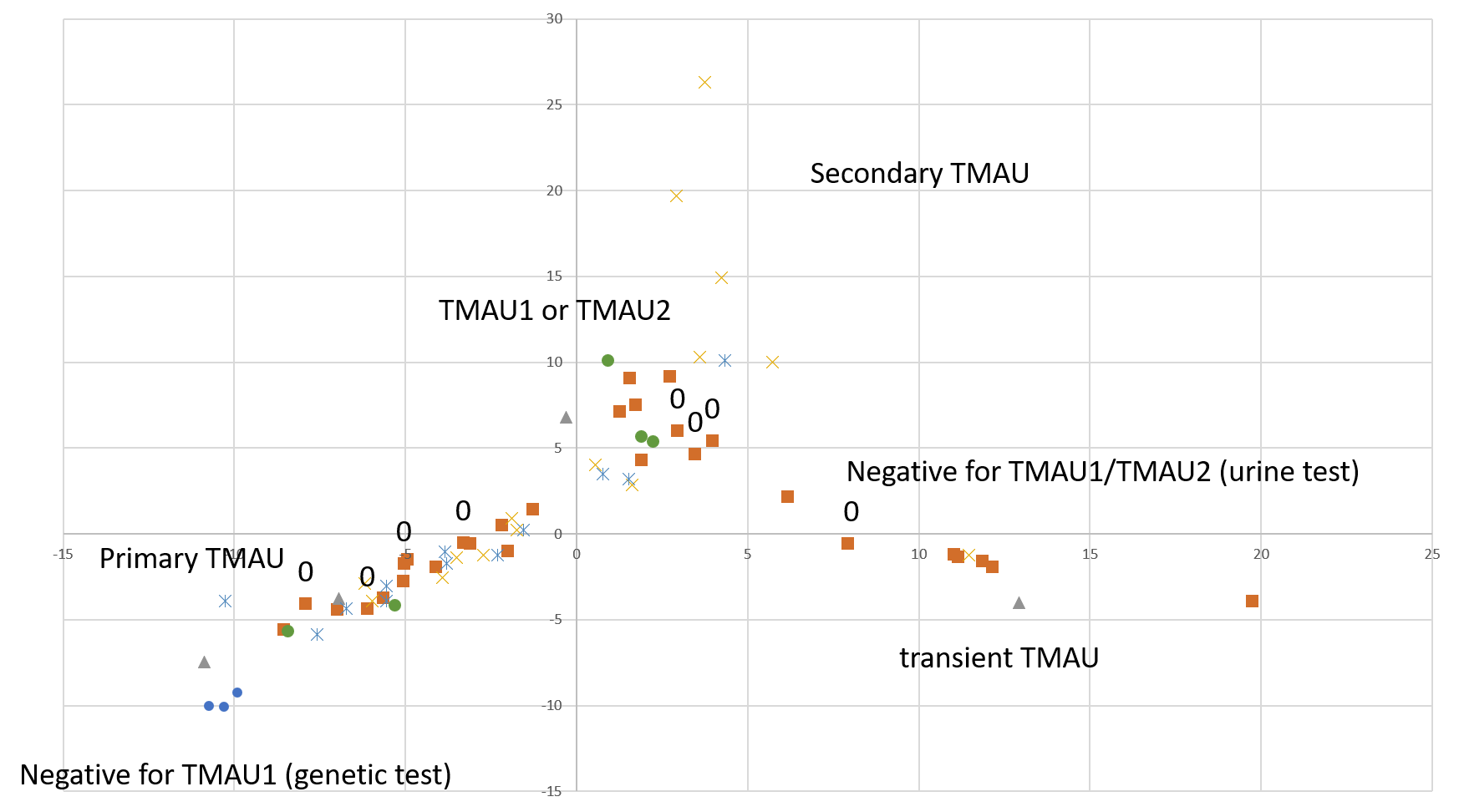

A quick-and-dirty principal component analysis of available samples vs all microbial species (figure on the right) shows that our research participants that tested negative for TMAU have different microbial profiles than those who tested positive, and microbiome for TMAU1 is different from TMAU2.

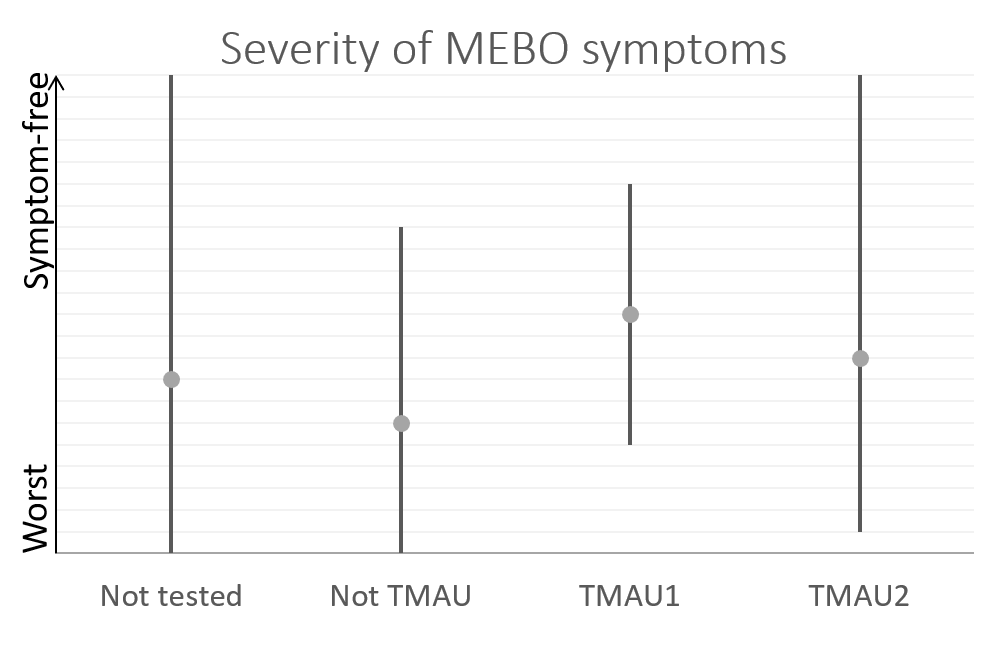

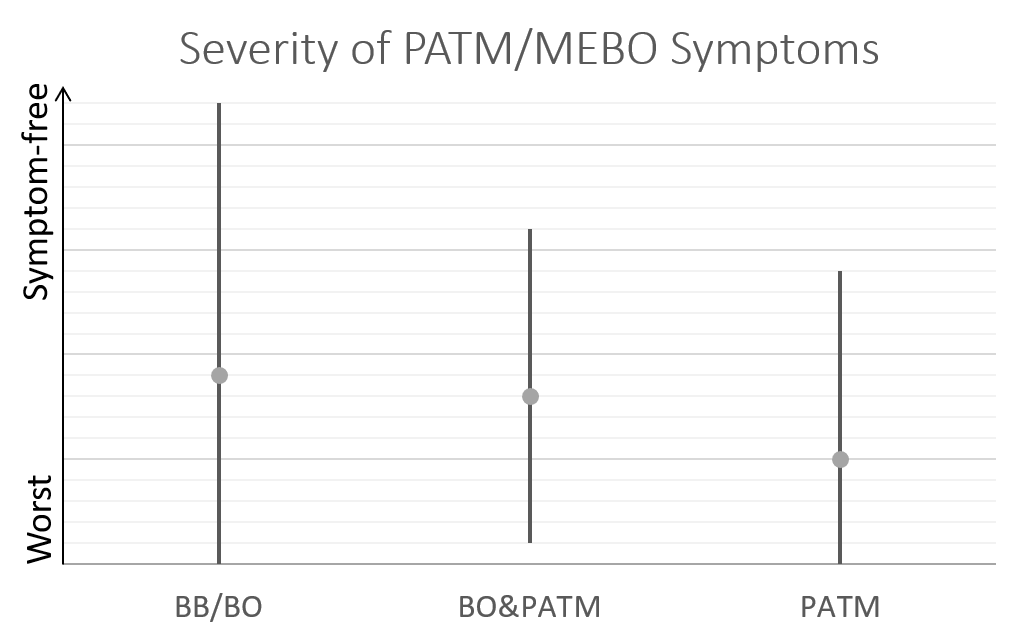

So far, we have over 40 samples of those negative to TMAU1 and TMAU2, and over 30 samples of those diagnosed as either TMAU1 or TMAU2, dozens of samples of those with PATM with or without body odor or bad breath. Interestingly these groups significantly differ in the self-perceived severity of their symptoms.

Average MEBO score is the worst for those diagnosed negative to TMAU. (The figures show average MEBO scores along with their variations) Surprisingly, it's the best for those diagnosed with the most severe form of TMAU - TMAU1! This shows that it's possible to learn to control symptoms even in extreme cases.

PATM symptom severity is even lower than MEBO symptoms for TMAU-negative individuals.

In our next posts we will be looking at the potential of microbiome for diagnosis of different sub-conditions, such as TMA1, TMA2, PATM and other subtypes.

We'll be also looking at different subgroups of bacteria - such as Enterobacteria that reduces TMAO to TMA Multiple research studies including correlation of metabolomic data from mixed microbiota fermentation systems did not give a true picture of which members of the gut microbiota were responsible for converting TMAO to TMA, and we hope to get a better insight.

Big thanks to all those who were able to complete the study - we know that it was quite a challenge for some! Thanks to those who contributed at least one sample along with the QoL questionnaire. Thanks to all who donated their samples, even though they had to pay for it out of their own pocket. Let's continue to work hard together to find the solution.

REFERENCES

Hoyles L, Jiménez-Pranteda ML, Chilloux J, Brial F, Myridakis A, Aranias T, Magnan C, Gibson GR, Sanderson JD, Nicholson JK, Gauguier D. Metabolic retroconversion of trimethylamine N-oxide and the gut microbiota. Microbiome. 2018 Dec;6(1):73.

Qiu L, Tao X, Xiong H, Yu J, Wei H. Lactobacillus plantarum ZDY04 exhibits a strain-specific property of lowering TMAO via the modulation of gut microbiota in mice. Food & function. 2018;9(8):4299-309.

Gabashvili IS. Community-led research discovers links between elusive symptoms and clinical tests. bioRxiv. 2017 Jan 1:139014.

Update on Clinical trial NCT03582826: Microbial Basis of Systemic Malodor and PATM Conditions

Recruited: 110 participants

Update on Clinical trial NCT03582826: Microbial Basis of Systemic Malodor and PATM Conditions

Recruited: 110 participants

Participated in the study (at least partially): 74

Submitted 3 or more samples: 48

Submitted 2 samples: 13

Submitted 1 sample: 13

Submitted 2 samples: 13

Submitted 1 sample: 13